When artist Francesca Balzan and curator Justine Balzan Demajo first discussed the idea of an exhibition at the National Library of Malta, they didn’t imagine copper wire from an old telephone would become central to the work. But the material found her – as materials often do.

“It was such a coincidence,” Ms Balzan says. “We had gone to GO’s offices to talk about a possible collaboration and ended up discussing all the waste products created in telecommunications — copper came up immediately. My antennae were raised. Copper is used so much in sculpture, and it’s a metal considered very valuable. I’m always thinking about how an ordinary object can have a perceived value that changes with time.”

Shortly after that meeting, she found herself offered a bundle of old copper wiring – not from GO, but from her mother in law who had been keeping it for years. “She’s an artist too, and she gave me this old wire. I love when coincidences occur in my art. As artists we have to keep an open mind and receive these coincidences.”

This unexpected material slowly rewired her new body of work.

Copper, clay, the unpredictable

Ms Balzan identifies first and foremost as a sculptor. While she works across materials, the past years have seen her explore clay and paper in increasingly intricate ways. Ahead of the exhibition, she had been sculpting porcelain flowers – “because I like gardens,” she laughs – and challenging herself to approach paper-like forms through clay.

And then copper entered the studio.

“I realised I could connect the flowers with copper,” she explains. “I started making the flowers with holes so I could weave the copper in. It completely changed the way I was working. Copper ages beautifully – it acquires a patina just by being exposed to water in the air. I’m very interested in materials that change with time. It changes unpredictably, and this as an artist is exciting.”

Malta’s national library

The exhibition Incunabula 1474–2025 was born a year and a half ago, when curator Justine Balzan Demajo visited the artist’s studio.

“She told me, ‘I have an idea – I’d like an exhibition at the Bibliotheca.’ I spent many years researching there as an art historian. It’s a place of undiscovered treasures. Many highs and lows in my career happened in that building. To return not as a researcher but as an artist… it was a dream.”

She knew instantly that porcelain would sit powerfully within the library’s dark shelves.

“Porcelain is considered valuable, and its thinness parallels the thinness of paper. That was important to me. The flowers, the hair on the busts… they all speak to fragility but also endurance.”

Among the library’s treasures is a remarkable collection of early printed works – incunabula from the late 15th century.

Ms Balzan and Ms Demajo requested access to sixty of these books. “We went through them page by page. I searched for characters from these books to rework in 3D printing.”

Technology in infancy – then and now

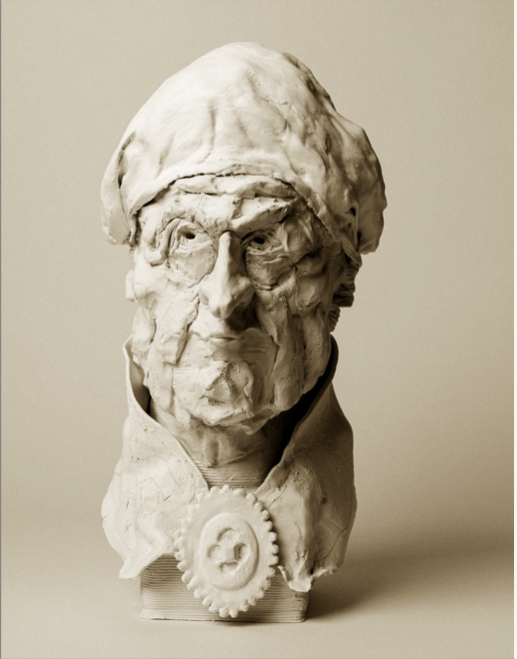

Ms Balzan’s porcelain sculptures in the exhibition merge with 3D printed clay forms – a deliberate parallel between two historical thresholds.

“3D printing in clay is still in its infancy, very much like printing in the 14th and 15th centuries in Europe,” she says. “It occurred to me that this new technology mirrors the brand-new technology of the 1400s. They both transform how we reproduce knowledge.”

Working with technologist Matthew Catania, she printed sixteen identical heads – then transformed each one by hand.

“I overwrote them with my hands,” she says. “I’m really concerned about the point of singularity. I feel we’ve arrived at it.

With this exhibition I’m saying that the human hand, heart and mind are still so important. Maybe tomorrow it won’t be the same. But for now, I can still override the machine in a way it can’t override me.”

Visiting the exhibition during GO’s 50th anniversary celebration at the National Library, I was struck by that tension she describes – digital precision threaded with the vulnerability of touch. The porcelain flowers, paper-like in their delicacy, sit beside faces that are beautiful, uncanny and almost tenderly grotesque. The copper glints quietly. And the works feel at home in the moody, book-saturated air of the Bibliotheca, where centuries of dust and knowledge linger.

Ms Balzan’s work is fresh and not nostalgic. It is attentive – to materials, coincidences, technologies, and the small interventions of the human hand. Each piece holds its own patina of time.

Portrait credit: Therese Debono

Other images: Lisa Attard

Main Image: